Acts of omission: How Pakistan fails to address impunity for enforced disappearances

Oct 9, 2022: 14 min read

One out of every 10 missing persons reported to the Commission of Inquiry was eventually traced to an internment centre.

By Reem Khurshid

Hasnain Baloch, 19, comes from a family of seven brothers. He has lost two of them; both disappeared years ago.

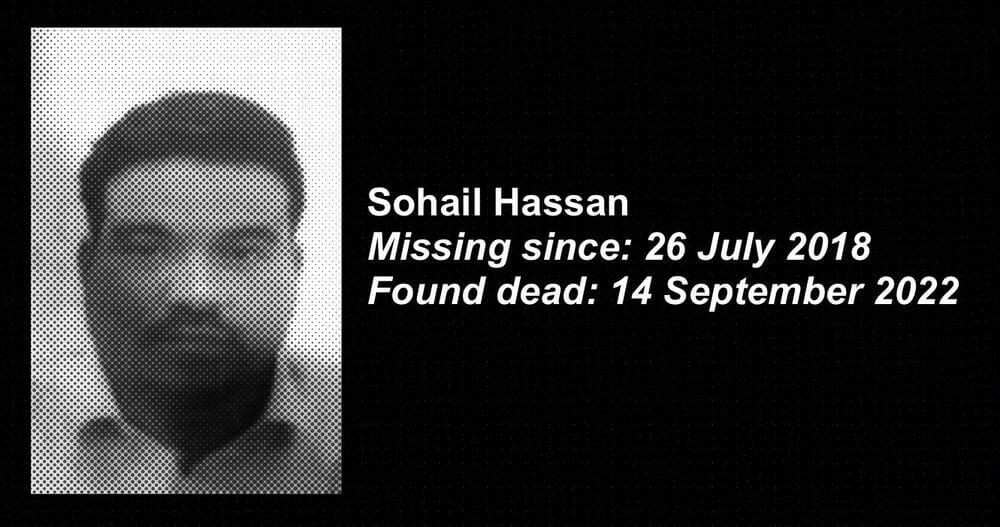

One brother, Sohail Hassan, 36, was among the dead when the remains of four men were discovered on roadsides across Sindh last month. He had been abducted from Pishukan, a village in Gwadar, Balochistan in July 2018, allegedly by security forces.

His other brother, Mohammad Hassan, who was 18 when he was taken in Karachi in 2016, is still missing. “We are a poor family, where are we supposed to go ? What door must a poor man knock on to ask for justice,” Hasnain says.

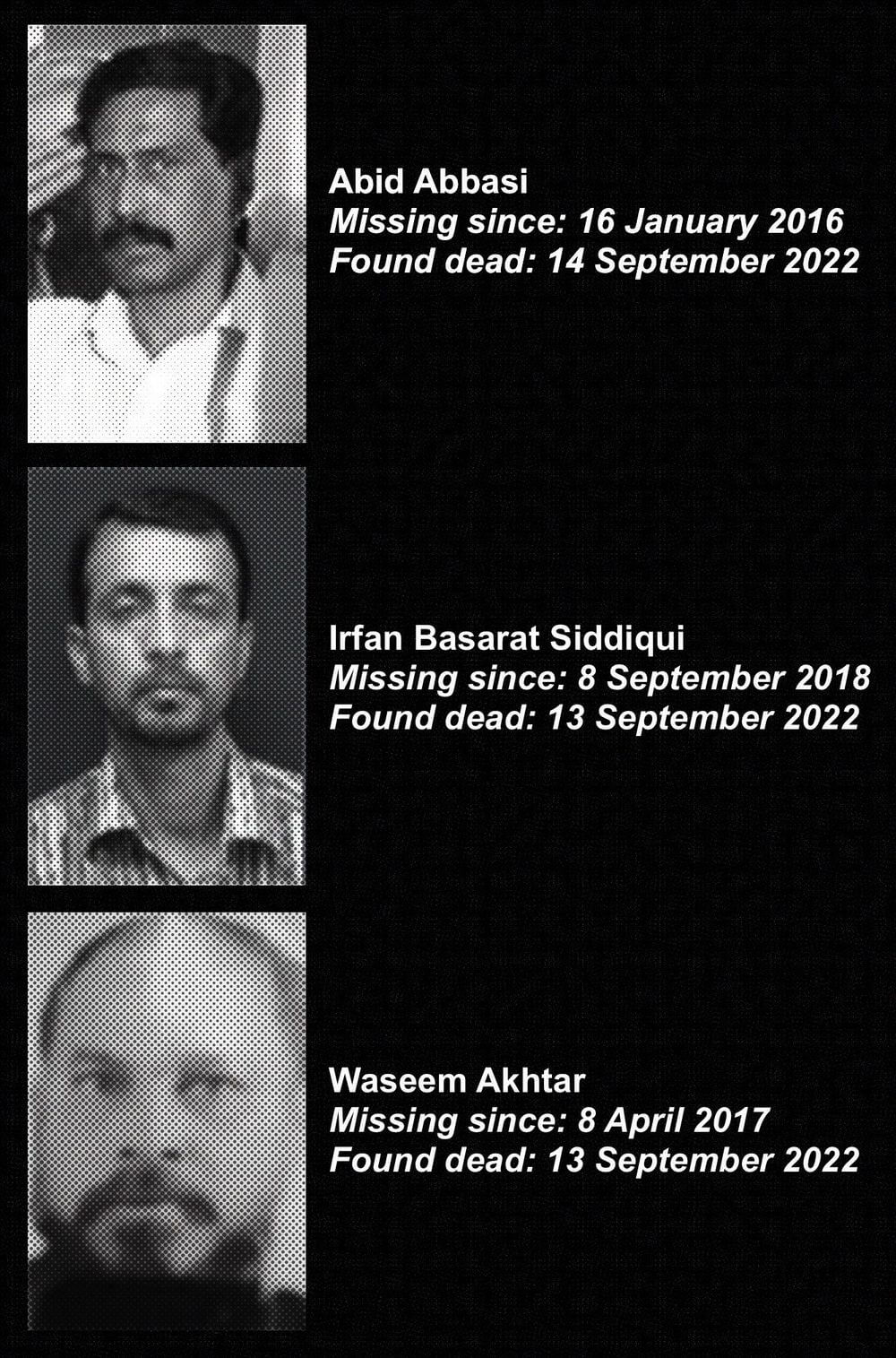

The other three men whose remains were found last month had all been workers of the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM) party. They were identified as Abid Abbasi, Irfan Basarat Siddiqui and Waseem Akhtar.

Speaking to Dawn News, leading member of the MQM-Pakistan faction and Minister for Maritime Affairs Faisal Subzwari confirmed that these men had been arrested from their homes several years ago, and had then vanished without a trace, until now.

All the bodies bore signs of torture. Human rights activists believe these cases have all the markers of an unofficial state practice of extrajudicial killing known as “kill-and-dump”.

The names of the three political workers were on a list of disappeared persons, a database of thousands of names, maintained by the Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances.

The Commission was established by the government in 2011 to locate “allegedly enforced disappeared persons” and to “fix responsibility on individuals or organisations” behind these abductions.

Since then, it has registered 8,699 “missing person cases”.

As of June 2022, it had resolved three-quarters of these cases, while 2,264 were still being investigated. The Commission had closed two of the MQM worker cases, stating that the complainants hadn’t attended any hearings. The third, Siddiqui’s case, was “under investigation”. Three months later, their bodies were found.

***

Earlier this year, I wrote to the Commission to request a copy of their missing persons case list, which had disappeared from its website around two years ago, citing the Right of Access to Information Act. The dataset was promptly uploaded to its website once again, and accessed by me on 20 June 2022. Unless otherwise stated, all figures cited are from the Commission. A copy of the cleaned data can be accessed here.

THE DISAPPEARED

These figures do not represent real-time information on each person, but the status of each case at the time it was closed by the Commission. Cases under investigation were still open as of June 2022.

TOTAL DEAD: 272

Dead bodies found: 164

Dead or presumed dead and legal heirs received compensation payment: 34

Died in an internment centre: 13

Died in prison: 5

Killed in an ‘encounter’ with law enforcement agencies: 56

TOTAL IN CONFINEMENT: 1,483

In internment centres: 893

In military custody: 43

In paramilitary custody: 33

In prison: 514

TOTAL DELETED: 1,349

No explanation provided: 76

Withdrawn by complainant: 64

Non-prosecution by or non-cooperation of complainant: 59

Incomplete or false address provided by complainant: 151

Not an enforced disappearance: 874

Not an enforced disappearance; person is at large: 57

Not an enforced disappearance; person has deserted their post: 10

Not an enforced disappearance; person has left the country: 34

Not an enforced disappearance; person is deceased: 12

NNot an enforced disappearance; person is presumed dead: 12

NO INFORMATION AVAILABLE: 122

TOTAL UNDER INVESTIGATION: 2,264

TOTAL RETURNED OR RELEASED: 3,209

Released after being held in paramilitary custody: 5

Released after being held in an internment centre: 11

Released from prison: 46

Released from prison on bail: 87

Released after being held by unknown persons: 301

‘Recovered’: 10

‘Traced’: 167

Returned home: 2,582

BRINGING UP THE BODIES

Sindh

The MQM says more than 200 of its workers have gone missing in the past three decades. Some returned alive, others dead; many are still unaccounted for.

The Commission of Inquiry has recorded 1,712 missing persons in Sindh. According to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan (HRCP), one of the earliest instances of mass disappearances occurred during the military operations to “restore law and order” in Karachi in the 1990s. The MQM said over 40 of its activists went missing during these operations.

At least 44 disappearances in Sindh during the 1990s were later reported to the Commission.In more than half of these cases, the provincial government eventually paid the relatives of the missing men Rs500,000 each.

The most reported disappearances(368 cases) occurred in 2015 when, on average, one person went missing every day.

While many have returned, few have spoken publicly about their abduction.

Since the 2010s, an increasing number of Sindhi nationalists have also gone missing, with families alleging they were picked up by security forces or intelligence agencies. The relatives association Voice for Missing Persons of Sindh has compiled a list of 366 enforced disappearances it says took place from January 2017 to August 2022.

While many have returned over the years, few have spoken publicly about their abduction, fearing reprisals. In several cases, the mutilated remains of missing persons have been discovered in apparent extrajudicial killings.

The Commission has located a little over half of those reported missing in Sindh. It says that in 729 cases, they have either returned home, been released from custody or have been “traced” without adding further details. There were 233 more people found in detention; while most were in prisons or police lock-ups, 32 were in Rangers custody, 28 in internment centres and four in military custody.

Eighty-three had died or were presumed dead; 42 bodies were recovered; 14 were killed in an “encounter” with police or Rangers, and two died in prison. In 25 cases the missing person was presumed dead and their relatives offered financial compensation.

The Commission has deleted 368 cases from Sindh, stating that it either had insufficient information to pursue an inquiry or that it was not an enforced disappearance.There is no information on the status of 64 cases.

It is still investigating 228 cases in Sindh.

Balochistan

Balochistan has just over 5% of the country’s population, according to the 2017 census, but it accounts for 21% of cases reported to the Commission. Of these 1,827 cases, most disappearances were reported to have occurred in 2017, when more than 800 people went missing.

President of the Balochistan National Party Akhtar Mengal recently told CBC that one of the earliest known cases of an enforced disappearance in the country was of his own brother. In February 1976, 19-year-old Asadullah Mengal and his friend Ahmad Shah Kurd were abducted by security forces. They were never seen or heard from again. The military has always denied its involvement in the disappearance of the two young men.

The HRCP noted that enforced disappearances in the province were reported with increasing frequency from 2005, coinciding with the start of the fifth Baloch insurgency, which continues today. Among the missing are doctors, teachers, students, artists, journalists and activists.

Ten percent of Balochistan’s cases have been deleted.

Mass graves were reported to the United Nations as early as 2011 and in 2014, locals stumbled on three mass graves in Khuzdar district. The provincial government said that 17 corpses had been recovered but Baloch activists disputed this, insisting that over 100 bodies were exhumed.

Citing figures from Pakistan’s Ministry of Human Rights, the BBC reported that at least 936 dumped bodies were found in the province between 2011 and 2016.

The Commission says that two-thirds of those reported missing in Balochistan (1,175 people) have returned home or been “recovered”. Twenty-three were traced in detention; two of them in military custody. In 33 cases, the missing person was either confirmed or presumed dead. No information was provided on the status of 14 cases.

The Commission has deleted 188 cases – 10% of the province’s cases – declaring that they were not enforced disappearances and thus did not need further investigation.

It is still investigating 367 cases.

So far this year, 312 cases of extrajudicial killings and 413 cases of enforced disappearances have been documented by the non-profit Human Rights Council of Balochistan. This brings its total number of disappearances since January 2019 to 1,733 and its total number of recorded killings also to more than a thousand.

Many families of the missing Baloch have boycotted the Commission, citing its lack of support.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

More than a third of all recorded cases come from Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP), where there have been over 3,000 disappearances, and where there are still 1,342 cases under investigation.

The HRCP noted that a large number of men in northwestern Pakistan first began to go missing in the 1980s, rumoured to have joined the war in Afghanistan against the Soviet Union. Whether they had gone voluntarily or not was unclear.

In the wake of the 2001 US-led invasion of Afghanistan, Pakistan began handing over suspected militants to the CIA. The president at the time, Pervez Musharraf, would write in 2006, “We have captured 689 [suspected members of Al Qaeda] and handed over 369 to the United States. We have earned bounties totalling millions of dollars.”

By late 2006, Pakistan’s Supreme Court began hearing petitions filed by relatives of the missing and human rights organisations. In March 2007, the same month he sacked the chief justice, Musharraf told a rally in Rawalpindi that allegations of enforced disappearances by the military were “sheer propaganda”, claiming that those who had gone missing had been recruited or lured into joining militant groups abroad.

The Commission’s own data shows that 34 cases were “not a case of enforced disappearance” as the person had left the country. Of these, 28 were reported to have gone to Afghanistan; only five were said to be engaged in militant activities.

The war in Afghanistan had profound consequences in Pakistan, particularly over the porous borders in the northwest, where the Pakistani Taliban had begun to seize territory and establish its own rule. By 2007, the military began conducting operations to take back these areas.

The highest number of disappearances recorded by the Commission occurred in 2009, when at least 636 people went missing. This was the same year the Pakistan military began conducting massive operations in the northwest of the country. Over two million people were displaced in the conflict.

More than 900 of the missing were traced to internment centres.

Internment centres were set up under special legislation (with retroactive effect from January 2008), which gave the military broad powers to detain alleged militants.

The Commission’s data shows 917 missing persons were traced to these centres in KP. Eleven were stated to have been released while 13 people had died in custody.

After the Army Public School massacre in Peshawar on 16 December 2014, Pakistan reinstated the death penalty and established military courts to try civilians accused of terrorism-related offences.

In January 2019, then head of public relations for the Pakistan military Asif Ghafoor told Dunya News that military courts have “no link with the issue of missing persons”. But a few months later, he told a press conference, “We don’t want anyone to be missing, but war is ruthless. Everything is fair in love and war.”

The Commission has traced 43 missing persons in military custody, just under half of them from KP. Of the six reported to have been sentenced to death, four were from the province.

Separately, the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) has recorded at least 3,801 missing Pashtuns as of May 2022, almost all of them from KP – about 500 cases more than the number reported to the Commission.

Alamzeb Mehsud, a founding member of the PTM, began collecting data on missing Pashtuns in 2016. “I meet with every family to collect details about their missing relatives. But we don’t record every case,” he says, pointing to situations where relatives or local jirga have been told that the disappeared will be released after a few weeks of questioning. Hence, cases that the UN describes as “short-term enforced disappearances” have not been documented.

The PTM says it has submitted cases to the Commission and the UN, and has raised them in meetings with representatives of the military.

‘DISPOSED OF’

In a briefing paper published in September 2020, the human rights NGO the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) delivered a scathing review of the Commission’s work, stating, “A commission that does not address impunity, nor facilitate justice for victims and their families, can certainly not be considered effective.”

It found that the Commission’s definition of enforced disappearances did not conform with international law, “leaving a potentially large number of victims outside of its purview”.

The ICJ also criticised how the Commission resolves cases.

It found that cases were “disposed of” without any apparent attempt to investigate further merely upon confirmation of the missing person’s whereabouts — whether confirmed dead or found to be in the state’s custody — despite the passage of many months or years since their abductions were reported.

Like the cases of the MQM workers whose bodies were discovered last month, other apparent cases of enforced disappearances have been closed without much justification.

In one case, relatives said that they could no longer attend hearings on their missing relative’s case in Karachi as they had moved to KP. “Accordingly, no further action is required. The case is closed,” the Commission wrote.

For over 15 years, the NGO Defence of Human Rights (DHR) Chairperson Amina Masood Janjua has campaigned for families of the disappeared and has worked closely with the Commission. Her husband, Masood Janjua, went missing in July 2005. On the Commission’s database, his case has been deleted, described as “not a case of enforced disappearance”.

“I was told conflicting things,” Janjua says. At times officials told her that they had no idea of his whereabouts, then that he had been killed in Waziristan by Al Qaeda militants without providing any evidence. “It’s a story they made [up],” she says.

The Commission has deleted cases where “all stakeholders denied arrest/custody” or has resolved cases with as vague an explanation as receiving “assurance that [the missing person] was being interned in some internment centre” and thus considered “traced”.

In fact, the Commission’s terms of reference are something of a catch-22. It can only “register or direct the registration” of a first information report (FIR) with the police against perpetrators of an “untraced” person – if “traced”, it no longer has the power to pursue legal action.

“The Commission is just a post office,” says Janjua.

While in most cases those who have returned home are reluctant to talk about their confinement (in at least 50 cases, the Commission states, “for obvious reasons”), there are several instances where the Commission appears to confirm the state’s involvement in these disappearances without judgement.

HRCP Chairperson Hina Jilani blames the Commission, saying it “has totally failed in recovering missing persons or taking any initiative to contribute towards prevention of enforced disappearances”.

Jilani accuses the Commission of effectively whitewashing cases of state abductions. “The data is totally misleading. Those stated to have been recovered are cases in which people have been genuinely disappeared by our intelligence agencies, and once they decide they no longer have use for these people they release them somewhere.”

Janjua says, “It is not the Commission’s pressure or efforts to which this tracing [of missing persons] is owed. It is the agencies themselves who decide their fate. The Commission is just a post office.”

Still, she says, DHR continues to work with the Commission because they feel it is the only avenue for justice that most families have access to.

Janjua also doesn’t believe the official figures reflect the actual number of enforced disappearances, explaining that many families do not approach the courts or Commission out of fear, or due to lack of resources, access and awareness. Relatives who do reach out to official channels, she says, are subjected to “degrading treatment”.

Mehsud echoes these concerns, “The Commission hasn’t fixed responsibility on any perpetrator. The families are persecuted, mistreated, told that their relatives have left to fight jihad. It is only there for lip-service.”

In a reply by email to a summary of these criticisms, the Commission cited its 75% case disposal rate as indicative of its “successful performance”, arguing that “cannot be termed as failure on the part of the Commission by any stretch of imagination.”

That relatives of the disappeared, including those referred by DHR, are still submitting cases, it said, “defuses the impression that there is lack of trust and confidence” in the Commission among the families.

It further claimed that its “sole mandate” is to trace the whereabouts of missing persons.

While the 2011 notification through which the Commission was established – including its full terms of reference, which specify fixing responsibility on perpetrators of enforced disappearances – is not currently available on its website, an archived copy can be accessed here.

When shown this document, the Commission responded that this phrase “ was only intended to prioritise [its] functioning” and that it “also works on” the other terms of reference.

The Commission has in the past claimed to have “taken action” against 153 army personnel, without furnishing any more details. The ICJ notes, “There is no other public record of such ‘action’.”

UNGRIEVABLE LIVES

Writing on enforced disappearances in 2010, the late activist I.A. Rehman noted that while “the authorities have chosen to quibble over the number of missing persons… in this barren debate what matters most is not always fact but the people’s perception”.

Enforced disappearances, whether five or 500, affect more than just those missing. Human rights organisations argue that the fear, insecurity and repression it foments, and the impunity surrounding these crimes, have profound impacts on whole societies.

They are acts of political violence, which HRCP and DHR both believe require a political solution.

Meanwhile, the relatives of the disappeared are forced to live with the uncertainty of not knowing whether to hope for their return or to mourn their loss.

Mehsud recalls one case in which, he says, a man was picked up from his relatives’ house in Rawalpindi, and sent to an internment centre in KP. Three years later his bullet-riddled body was found in the mountains, in the same clothes he had been wearing the day he disappeared.

“Believe me, when his body was brought home, the happiest faces there were those of his parents,” says Mehsud. “At least they had a body. At least they knew what had happened to him.

“Just tell the truth. Tell us if these people are dead. That’s all we demand – the truth.”